Commusings: The Mosquito Bites an Iron Bull by Jake Laub

Dec 11, 2021

Hello Commune Community,

When I use the word yoga please don’t misconstrue it for pretzeling yourself into a human knot. Yoga (Sanskrit: to yoke) is, quite simply, union – ultimately a sensation of samadhi or integrated consciousness – when the illusion that you are a separate self melts away. Along the highway to this somatic satori, the yogic path offers myriad roadside rest areas to experience unification of mind and body, nature and yourself, light and shadow and, inevitably, life and death.

The commodified yoga of the West is too often redolent with the ego’s perfume. Its objectified, lithe, lycra-clad forms, its whimsical handstands, its bespoke accessories are designed for the gaze of others. Of course, when we identify with the ego that tells us we are what others think, or what we have, or our position in society, then we doom ourselves to another form of exercise: running on a hedonic treadmill with no stop button.

In this week’s missive, my dear friend Jake recounts his journey out of the performative and into the reformative, a process of “reforming” the self as something seen in one’s own eye and not through those of others. This process is none other than the practice of yoga itself.

Send me a note by pigeon or at [email protected] and follow my daily exhortations on IG @jeffkrasno.

In love, include me,

Jeff

• • •

The Mosquito Bites an Iron Bull

From Ballet to Yoga, the Hard Way Around

By Jake Laub

I used to have four extra bones in my feet. Now I have three — but I’ve decided the rest can stay where they are.

In some ways that fateful fourth bone was doomed the moment my mother called our small town dance academy and asked:

“My 10-year-old wants to join a ballet class, do you have space?”

“Sorry, we’re all full for the quarter.”

“Oh, he’ll be so disappointed.”

“A boy? Bring him in.”

During my first class the teacher took off my leather slippers and, while 15 girls in pink tights watched, jammed her fingers between each and every toe, painfully stretching the webbing, frog-like.

Ten years later, a different, yet equally imposing artistic director looked me over during my first company class, grabbed a solid handful of my right thigh and said, "We are going to take these muscles, and move them over here."

Ballet was less fun than … pretty much anything else I could think of doing once I was a decade in, but I was strangely committed to the magic of making something incredibly difficult look easy. And so when a variety of shooting pains began to develop in my ankles, I lowered my head, popped Ibuprofen, and plowed through my pliés. The women of the company bled through the lambswool stuffed in their pointe shoes. Who was I to complain?

Pain in the wings, grace on stage. Two sides of the same coin.

X-rays revealed those four extra bones in my feet: two “accessory naviculars” on the inner arch of the foot and two “os trigonum,” accessory bones that develop behind the ankle.

(Brief aside: Your body does not match the muscle and skeleton posters in your massage therapist’s office. For example, os trigonum is present in approximately 15 to 30 percent of the population, but it’s mostly asymptomatic except in ballet dancers and soccer players who tend to extremely impinge the back of the ankle. Many of you are walking around with a non-standard number of ribs. Or a psoas minor. Or an extra pec muscle called the sternalis. The list goes on. My model skeleton is named Norm so I can remind people — “None of you are the Norm!”)

I opted to remove the left os trigonum, the most painful of the three. At 24 years old I remember leaping off stage after my final performance before surgery thinking, “I’ll never be this good at this crazy skillset again.”

Like any good dancer, I took to rehab with the same determination I poured into ten thousand hours of rehearsal. Though, with at least some degree of maturity and self-compassion, I decided I was ready to frolic in the greener pastures of modern dance (or, more accurately, to roll around on the floor).

So I moved to New York, and while working my way into the modern dance scene, I took up yoga. A professional-level modern dance class in the city cost $20, but I could roll out my mat at Yoga to the People on Saint Marks Place for a $2 donation and then eat a $2 falafel downstairs at Mamoun's, making for a sub-$5 Saturday morning.

I quickly learned, however: A good dancer is not automatically a good yogi.

Here is why I thought I would be good at yoga:

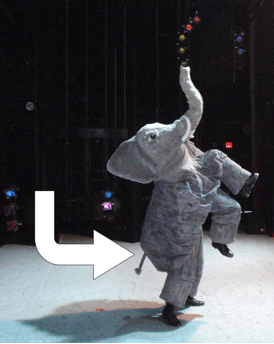

“I will probably be good at yoga because I am a dancer and dancers are good at everything because I am more flexible than 95% of the people I know and a dance teacher made me do some yoga poses once and they didn’t seem too hard. Also, if I can tap dance blind as the back half of an elephant and deadlift a ballerina from a deep squat, surely I can learn a sun salutation and do chair pose with my eyes closed.”

Yoga can't require more coordination than this, right?

And this is me after trying yoga for a month:

“Why can’t I hold my arms above my head in external rotation for more than 30 seconds? Why have I never noticed that I can’t stand with parallel feet? Why is a proper hanumanasana so much harder than the splits? How is it possible there are so many nooks and crannies of my body I have never stretched before?”

And this, I realized, is the fundamental disconnect:

Yoga and ballet are so far apart on the movement spectrum that they curve around and settle next to each other in our minds. Kind of like how the political far left and far right can act in surprisingly similar ways even as they hold diametrically opposing values. The spectrum is U shaped, but you can’t simply hop over the gap.

There are many similarities between ballet and yoga – an emphasis on precise body alignment, breath technique, mental focus – but at its core yoga is about your relationship with yourself, and ballet (and professional dance in general) is about how your body looks to other people.

Yoga is inward – “What new domains can I explore within my body? How am I reacting to this pose or breath pattern in this moment?” There is no absolute right or wrong.

Professional dance is outward – “Is this what my choreographer wants? Do I look fabulous?” The audience is always right.

That form-over-feeling mentality, backed by years of stage training, was ultimately the last aspect of my dancer-self to soften. Within a year my shoulders had opened, my hips had realigned and my wrists could hold me in handstand. But even then the yoga teacher was always my director, the sequence my choreography, and the yogi next to me my audience.

It wasn’t until at least five years into my yoga journey that I let myself be guided on the mat by internal goals as opposed to external ones, that how I looked to myself inside was more important than how I looked outside.

It was a long journey, but eventually I trekked all the way around the U.

• • •

I wrote an outline of those last few paragraphs in my journal seven years ago, and I remember feeling rather smug about the progress I was making. But, oh how yoga is an onion. You cry peeling off every layer.

It’s true that I gradually let go of the performance value of my practice, and when a teacher might approach me after class and say, “What a beautiful practice you have,” I genuinely felt self-conscious and somewhat embarrassed.

But gradually, as I continued to be drawn toward ever more esoteric and rigorous asana practices, I realized that on my inward journey I have met an even more subtle and draconian artistic director — my own sense of sensation.

I am a sensation junkie.

In a way, an adoring audience is addictive because it is such a crude and obvious form of validation that what you are doing in life is worthwhile and has meaning. You perform and they applaud.

But pain, in a weird way, can serve a similar function.

Why is it so hard not to stick your tongue in a slow-healing sore even though you know that makes it worse? Why do we rub ourselves raw on our own negative thoughts?

Some of us can’t help licking the knife's edge of sensation, just to make sure it’s still there.

I now can see that in trying to be present and awake in my body I often seek intense sensations because in doing so I am so much more clearly ALIVE. Anything less than burning, aching, or straining is an anti-sensation. The audience isn’t applauding.

If I’m honest with myself, this is still where I am in my journey — somewhat stuck in this layer of the onion. Every once in a while I even find myself making a mighty effort to be easeful.

The wisdom of Zen philosopher Alan Watts is helping, though. He says, “So here’s the problem. I come and say to the teacher, ‘Teach me not to grasp.’ He says ‘Why do you want to know?’ And he shows you that the reason you want to stop grasping is that it’s a new form of grasping. … So [you realize], there is nothing I can do about it, and there’s nothing I can not do about it.”

You bind yourself so tight as you vacillate between the extremes of the paradox, that eventually you simply let go of the entire paradox itself and accept the inseparable yin-yang interconnectedness of the lived human experience.

Pain in the wings, grace on stage. Two sides of the same coin.

In Zen this revelatory predicament is apparently called “the mosquito trying to bite an iron bull.”

At some level you must exert effort to be effortless. But also, no effort is required.

What a dance!

Leading teachers, life-changing courses...

Your path to a happier, healthier life

Get access to our library of over 100 courses on health and nutrition, spirituality, creativity, breathwork and meditation, relationships, personal growth, sustainability, social impact and leadership.

Stay connected with Commune

Receive our weekly Commusings newsletter + free course announcements!